Knowledge transfer in software development hits me the hardest right at the beginning of a project – in that moment when a lead lands on my desk and I try to make sense of a few sentences, a PDF, or a half-remembered conversation from a conference corridor. Before any line of code exists, before any official “project” begins, there is already an intensive learning process going on between the client and the IT organization.

In our case this is usually custom, tailor-made software. We are not heavily productized as a service organization. That means each time I go through this, the discovery flow, the design operations, and the project management approach have to be aligned to a specific context, not to some idealized “standard project”. We build primarily on top of our learning experiences.

Alongside running Effect-Driven Design – my UX studio – and WCAGLab, the accessibility implementation brand, and leading discovery in a software development company, I am also working on a PhD at WSB University on knowledge transfer in software product creation, especially the learning process linked to AI. So I constantly watch these early stages as a kind of real world laboratory for organizational learning and knowledge management system in IT.

Knowledge transfer as the backbone before any code is written

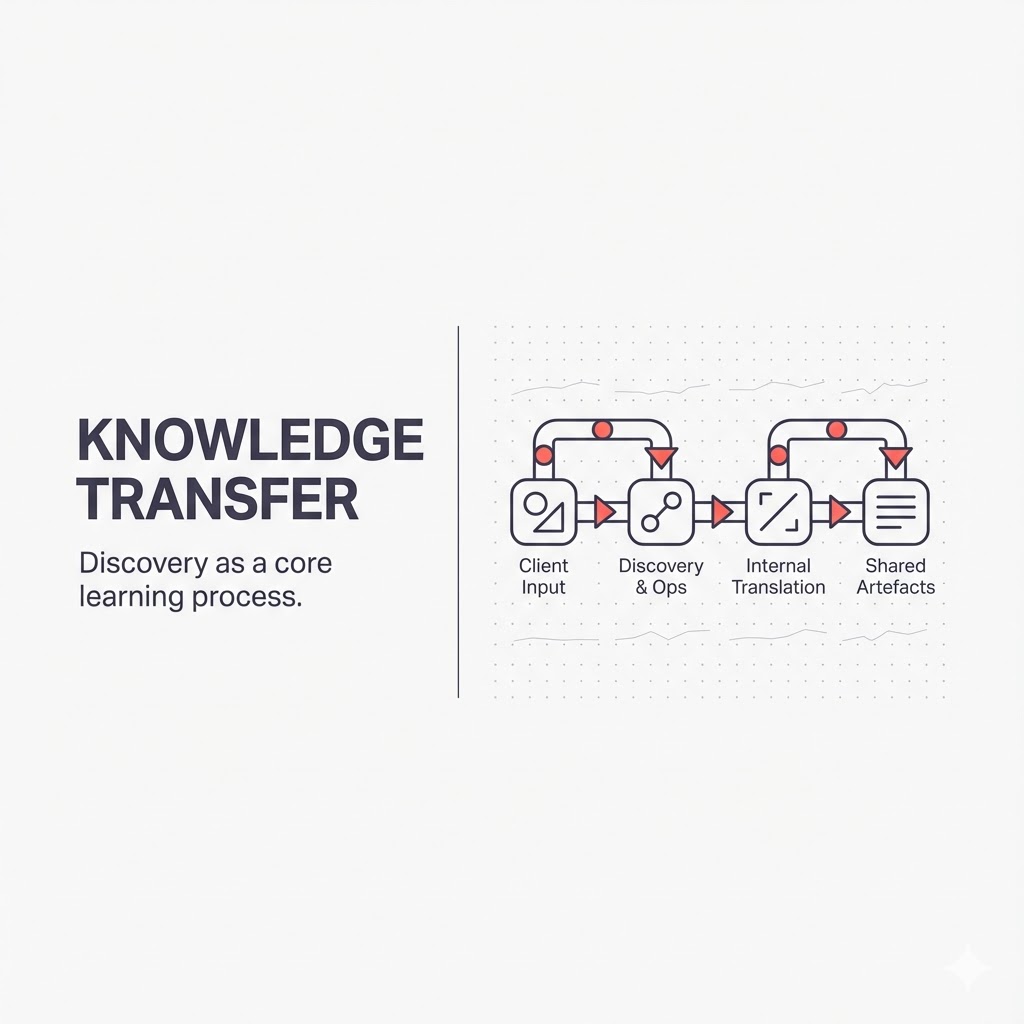

When I look at our software development process through this lens, one thing is obvious: until the source code is actually written, we mostly operate in the space of interpretations. What the client says, what they send over as documentation, what I hear, what I filter, how I retell the story inside the company – all of that is still knowledge transfer, not implementation.

It is a multi-layered exchange. On the client side, someone interprets business needs or board-level strategy and compresses it into a request. On our side, I interpret this request and pass it further to technical leads, designers, project managers. Every step is a potential distortion, but also an opportunity for learning if we are conscious about it.

Thinking about software development as knowledge transfer first, and only then as coding, gives me a surprisingly powerful diagnostic tool. Instead of asking only “where did the plan fail?”, I can ask “at which handover did knowledge actually get lost or misaligned?”. That is the core of organizational learning in this context.

From lead to first briefing: how discovery really starts

In practice, in our IT service company, everything begins with a lead. The path a lead takes is already part of the story. Sometimes I meet someone at a conference; we talk for twenty minutes, they sketch their pains and ambitions, and a few days later I get a follow-up email. Sometimes a structured enquiry lands in our inbox with an attachment, short scope description, maybe a non-disclosure agreement. Sometimes it is something far more formal like public procurement documents with detailed conditions of the order.

That lead usually reaches people in business development or partners group first and then is forwarded to me or someone else responsible for discovery – you could call it delivery management, discovery management, early project management, the label is less important than the role. If the topic has a strong design, UX or accessibility angle, it almost always lands on my table. When the conversation reaches a level where technical depth matters, I pull in one of our solution architects or tech leads.

Already here we have multiple layers of knowledge transfer: from the first contact on the client side, through whoever forwards it internally, to me, and then further. If I were to draw it, it is not a straight line; it is a small network of people with different perspectives passing context around.

Tailor-made software and why one fixed process does not work

Because we work with custom software development rather than rigid packages, I cannot simply push every project through one fixed discovery funnel. Productizing services in IT has its advantages, but in our case would lock us into one or two service processes that might not fit the reality of our clients. Right now our method is deliberately more open, less constrained. There is a cost to that, but the benefit is that we can match knowledge transfer and discovery depth to the real risk and complexity of the project.

Every time I start that initial analysis, I begin with whatever the client has already provided. That could be a few lines in an email, a handout from a talk, a call where they explained their idea, or a long functional specification. Often I need two or three conversations before I feel comfortable even thinking about an offer. The first contact is rarely enough for serious estimation and planning.

After those conversations I sit down, usually with one of the partners who also acts as tech lead or solution architect, and we talk through what I have picked up. At that moment I am basically a carrier of knowledge between the client and the person responsible for technical estimation. It sounds simple, but this is where a lot of organizational learning really happens.

Explicit and tacit knowledge in the first discovery conversations

On the surface we talk about scope: what features, what modules, what kind of users, what systems they already have. That belongs to explicit knowledge – something that can be written down, described, documented. Many of our clients are fairly mature in this sense. They bring a functional scope that is more or less documented, even if imperfect. My first job is to read and understand it, and cross-check it with what I heard verbally.

But very quickly I start hunting for tacit knowledge – things that are not written down, but completely change how we should approach the project. In these early discovery conversations I ask a lot of “why” and “tell me about the last time…” type questions. Why do they want this particular software now instead of a year ago? What exactly is not working in their current process? Which system did they previously use and what was great or terrible about it? Which ecommerce store or SaaS product feels like a reasonable comparison in terms of scale?

Those stories, analogies and episodes are what I often rely on to understand the real shape of the system. If someone tells me they want an online shop, but then references one specific marketplace as inspiration and another one as something they absolutely do not want to copy, I learn more from that pair of names than from a generic “we need an ecommerce platform”.

Tacit knowledge also appears in the way people talk about priorities. When they repeat certain constraints or concerns, when they hesitate at specific topics, when one phrase shows up in every meeting, that tells me where the real organizational pain points are. As someone who splits time between design operations, software development discovery and project management, I see my role as actively surfacing this tacit content so that it can later be transformed into more usable, explicit knowledge for the rest of the team.

Translating client reality into internal organizational learning

Once I feel I have enough of a picture, I move into internal translation mode. This is where knowledge transfer shifts direction: from “client to me” to “me to my organization”.

I collect my notes from calls, reread emails, revisit any documents they shared, and sometimes re-listen to audio from meetings. In parallel I sketch rough structures: flows between systems, possible user journeys, list of main actors and their goals. This does not have to be beautiful design work yet; it is still part of discovery and organizational learning.

Then I sit down with the architect or tech lead and describe the whole thing. I do it verbally, in my own words, but I support myself with sketches, sometimes quick diagrams, sometimes even very rough user stories. Because I have a software background and have written code myself, I know which details are important to highlight and which ones are noise at that stage.

At this point I am already consciously compressing and filtering knowledge. The architect does not need every anecdote; they need clarity on the main goal of the system, the approximate functional scope, the amount and nature of integrations, any non-functional requirements like performance or accessibility, and the constraints around budget or time. I try to give them exactly that, plus a sense of scale and complexity. That is another transformation of tacit into explicit knowledge, and another step in the organizational learning spiral.

There is also an important detail here: very often the person I speak to on the client side is not the final decision maker but someone like a marketing director or internal project manager. They already interpret the expectations of their board or stakeholders. So by the time the information reaches me, it is sometimes already second-hand. When I then pass it to our technical team, it becomes third-hand. Being aware of this chain helps a lot in correcting misalignments early.

Estimation as a mirror of our knowledge transfer quality

Based on this internal briefing, the architect or tech lead starts building an estimate. This is where software development, project management and knowledge transfer collide in a pretty unforgiving way. Estimation in IT is difficult even with perfect inputs. When the knowledge transfer is shallow, it becomes essentially educated guesswork.

The architect looks at the number of features, the volume and depth of integrations, potential technical risks, the technology stack we would use, and compares it with similar projects we have done in the past. That historical experience is another layer of tacit organizational knowledge that we draw on.

From that they derive an effort estimate in person-hours or person-days. Then we layer on top additional elements that are not “pure development”: time for project management, communication, coordination, time for testing and quality assurance, and a buffer for risk. Fixed-type projects add another dimension of risk because they push us to be especially careful in what we commit to.

For me, this estimation step is a kind of mirror. If we struggle heavily, if everything is vague, if the risk buffer needs to be absurdly high, it usually indicates that somewhere earlier the knowledge transfer in discovery was not deep enough. If we can express assumptions clearly, and both sides understand the uncertainty, then it means the organizational learning up to that point has been relatively successful.

When we do not know enough: discovery workshops as structured knowledge transfer

There are many cases where I simply have to say: we do not yet know enough to price this responsibly. In those scenarios I treat the discovery phase itself as the main “product”. We suggest a separate, typically fixed-price discovery engagement with workshops and analysis specifically designed to increase our shared understanding.

Because we deal with bespoke software, these workshops cannot be formulaic. The exact form depends on the domain, stakeholders and context. The common pattern is that we expand the group on both sides. On the client side, we might invite people from operations, support, IT, maybe someone closer to end users. On our side, I bring in UX designers from my team, a technical lead, sometimes a tester or DevOps if infrastructure and deployment will play a big role.

During these sessions we rely heavily on visual and collaborative methods. We sketch flows, draft simple mockups, map functional and non-functional requirements, and check our understanding of priorities. The goal is not just a nicer workshop report. The goal is to deepen knowledge transfer, surface tacit understanding about how the client organization really works, and move as much as possible into explicit, shareable artefacts: wireframes, structured requirements, clearer definitions of success.

Internally, this is also design operations in action. We are not only designing interfaces; we are designing how knowledge flows inside the project, how decisions are made, how the project management rhythm will work later. Discovery is not separate from operations; it is the first iteration of those operations.

The offer as the first shared knowledge artefact

Once discovery – whether lighter or deeper – gets us to a certain level of clarity, the direction of knowledge transfer flips again. Up to this point the main motion was client to us. Now it becomes us back to the client.

We prepare an offer that captures our understanding of what is to be built, describes the proposed software development process, explains the design operations we suggest (for example how UX, research, and accessibility will be integrated), and outlines the project management structure and responsibilities. It includes financial terms, scope, timelines, and sometimes multiple options.

I see this offer as more than a sales artefact. It is the first stable, sharable expression of a shared mental model between two organizations. Different people on the client side can read it and align. Different people on our side can refer to it once the project starts. It freezes, in a good sense, a snapshot of the current state of knowledge transfer and organizational learning.

Later, when a project manager joins, when developers or testers come on board, when new stakeholders appear on the client side, this offer often becomes the base reference. In that sense, it closes the initial learning loop: from first lead, through discovery, through internal translation, to a transparent proposal that can then be used to start the actual software development work.

Why I keep coming back to this lens

In many of my posts I circle around design operations, research ops, tenders, RFPs and the day-to-day reality of product and software development management. Underneath all of this I see the same pattern: what really differentiates good IT organizations from the rest is how deliberately they treat knowledge transfer.

Discovery is not just a pre-sales formality. It is a core learning process. Design operations are not just “how designers work”; they are about how knowledge flows through user research, UX decisions and implementation constraints. Project management in IT is not just ticking off tasks; it is about maintaining and updating a shared understanding of reality between everyone involved.

Looking closely at the first briefing, the early discovery conversations and the internal handovers gives me very concrete material for my PhD research on knowledge transfer and organizational learning in software development. At the same time it helps me improve how I run projects day to day as a founder and as a lead in an IT service company.

And this is why I wanted to unpack this specific phase here: not as a theoretical model, but as a real sequence I go through every week, where discovery, design operations, project management and knowledge transfer are not separate disciplines, but one intertwined learning process that starts long before the first commit appears in the repository.

Further reading

Read about basic concepts of knowledge transfer here

More about my space of research and beginning of PhD journey here

Our process of delivering accessibility

“Knowledge is the currency of the future.

Leave a Reply